Analytical knowledge and synthetic knowledge

In previous documents and articles on this site we have pointed out that a concept such as space-time, a fundamental concept of the theory of relativity, could not be synthesized by our mind, whereas mathematics, a human activity involving our mind, made a very precise analytical description of it.

This point seemed paradoxical to us, but we pointed out that analytical knowledge is not necessarily at the same level as synthetic knowledge.

An analytical knowledge of the object under consideration implements knowledge, which can be considered as properties of the object that can be considered as sub-objects.

But this « synthetic » knowledge of these properties requires less knowledge, since they are only a part of the object that we seek to know synthetically, which in general is more than the « sum » of the properties.

We could say that the analytic knowledge of an object is the knowledge of its properties including the possible relations with other objects.

Since in physics it is the proper and relational properties that matter, one could consider, although frustrating, that synthetic knowledge is secondary.

But is this true, or just an argument to clear us of going further?

The Allegory of the Puzzle

If you have a puzzle, you can assemble it from any first piece. You have to find another piece whose cut matches and whose pattern (drawing) is continuous (in general) with that of the first piece and so on.

It can be long but this method inexorably allows you to build the puzzle, without even knowing what the puzzle represents.

Is the Puzzle assembled, is the image it shows us intelligible to us?

Can our mind give it a unique meaning, when we know how it works to recognize images.

Associated with the perception of the image of the puzzle and the modeling it makes of it, our mind looks for a best matching with it (best fit with a model that it knows and that has meaning for it), but there can be several solutions.

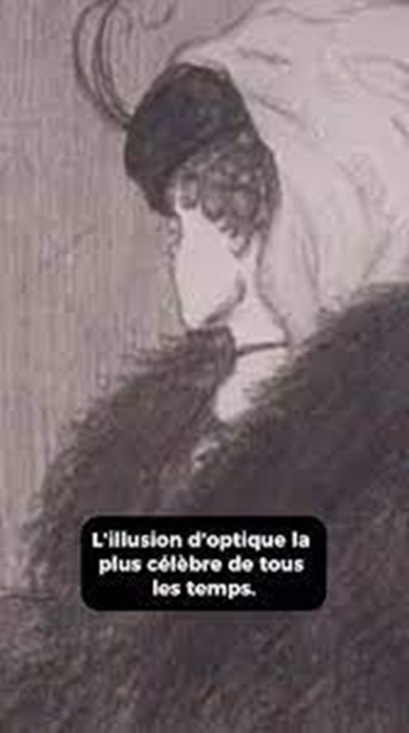

There are well-known tests where one image can represent two different figures.

In the example below, which is very well known, our mind identifies either a young woman’s face or an old woman’s face and we know that we will sometimes choose one, sometimes the other, but it will never present us with a « superposition » of the two images: it has made a synthetic choice from the same analytical information (same image).

This choice is restrictive (in synthetic information) because it presents us with only one of the two possible solutions.

This is an example where analytic knowledge does not univocally define synthetic knowledge, which argues for considering them of different natures as we suggested.

Note the similarity with quantum mechanics where, in a state of superposition of two eigenstates of the system, an experiment can only give one eigenstate, each with a certain probability.

Here, experience is the way we look at the image.

One look can give the young woman, another the old woman. Studies have shown that depending on who is looking, who may be young or old, the probability of seeing the young woman rather than the old woman is different, which shows that the objectivity of the result is biased by the subjective nature of our mind.

Moreover, if our mind does not find a reference that is sufficiently close to the image it perceives, what will it do, what will it produce?

Will it have a link with some reality, to be defined, and we will have to consider it as an image of reality, whereas being a production of our mind, it can be totally subjective and aberrant.

These are some questions that can reasonably be asked.